Covid inquiry report: We planned for failure

Deliberative public engagement is now needed to inform the values and objectives underlying prevention strategies for future emergencies

This post first appeared as a commissioned opinion piece in the British Medical Journal (BMJ 2024;386:q1633).

*****************************************************************************************

The UK Covid-19 Inquiry has published its module 1 report on the resilience and preparedness of the UK.1 The report is clear and thorough, finding nine major flaws and making 10 recommendations.

Much has been made of the UK “planning for the wrong pandemic.”

In fact, the core problem is that there was never a plan to prevent or control a pandemic at all—of any disease type.

It was never part of the plan to prevent or reduce pandemic deaths

In chapter 3 on risk assessment, Heather Hallett, chair of the inquiry, wrote,

“Planning was focused on dealing with the impact of the disease (in this case, influenza) rather than preventing its spread. As a consequence, the levels of illness and fatalities of a pandemic were assumed to be inevitable and there was no consideration of the potential mitigation and suppression of the disease.”

In chapter 4 she says that under the existing flu plan, up to 837 500 deaths were anticipated in a reasonable, worst case scenario. This is more than three times the 230 000 or more people who have died from covid-19 in the UK to date. Hallett then says:

“When it was said that the UK was well prepared before the covid-19 pandemic, this meant at the time that the UK should have been able to manage the deaths of this number of people—not that it was prepared to prevent them.”

It could not be clearer: over 800 000 pandemic deaths were considered an acceptable outcome and the plan was concerned with how best to cope with that number. During the inquiry, former health secretary Matt Hancock called this a “flawed doctrine.” Chris Whitty, chief medical officer for England, and John Edmunds, professor of infectious disease modelling at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, testified that not enough consideration had been given to prevention.

The possibility of legal quarantine measures was considered so extreme that they were mentioned only in passing and there was no strategy for use of other non-pharmaceutical interventions such as contact tracing or border controls. In 2017 and 2018 the World Health Organization specifically recommended that countries plan for a range of pathogens, including coronaviruses. Notably, Hallett found that there were lessons readily available from SARS-CoV-1 and Middle East respiratory syndrome, specifically around the efficacy of isolation and contact tracing, that would have left the UK better prepared to control SARS-CoV-2 had they been heeded.

When reality hit, the plan crumbled

The plan, based on coping with pandemic deaths rather than reducing them, crumbled quickly in 2020. Legal isolation measures (lockdown) were imposed at the threat of 500 000 deaths occurring in a “do nothing” scenario. This meant that a huge amount of crucial policy was made on the hoof—not just the legal orders to isolate, but moving to remote education; decisions on key workers, furlough, and border restrictions; how to communicate new rules and the latest data; and many more aspects of our response.

These strategic flaws meant that some of the most vulnerable people were left exposed: care home residents; care home workers who struggled to isolate with no sick pay; key workers who could not stay home and had no access to personal protective equipment; those who struggled to isolate effectively or work or learn from home; those in difficult circumstances such as living in institutions (including prisons); people who were homeless; or those living in violent households. All of these people fell through the gaps because no effort was made to think through potential policies and to plug the gaps before covid hit.

As Hallett says:

“The strategy was beset by major flaws, which were there for everyone to see. Instead of taking the risk assessment as a prediction of what could happen and then recommending steps to prevent or limit the impact, it proceeded on the basis that the outcome was inevitable.”

Who decides how many deaths are acceptable?

If the flaws were there for everyone to see, how did we get into a situation where no one involved in pandemic planning questioned the assumption that almost a million deaths were acceptable? While part of the problem is doubtless that the different expert bodies involved in the process had too narrow a remit and no overarching oversight, another key problem is the lack of a clearly defined and transparent objective for pandemic planning.

In an emergency situation, objectives will speak to core values (such as how lives are valued, and whose, or how trade-offs between the burden and costs of policy measures and potential lives saved are evaluated). When the pandemic hit, the values that informed pandemic strategy and policy were not stated and nor is it clear whose values they were—the government, the health secretary, parliament, the public?

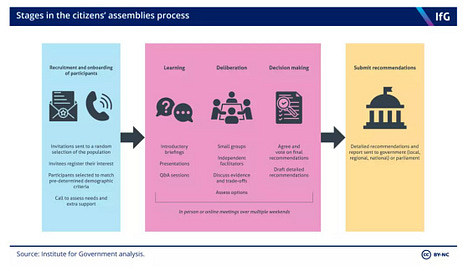

This needs to change. Public deliberation is needed in advance—before the emergency. Whether the emergency is a pandemic, climate emergency, terrorism, or something else, the policy options involve complex problems, uncertainty, and difficult trade-offs. The population needs to buy into these policies—for legitimacy and successful implementation. Hallett also recommends that the public be “consulted, engaged with, and informed about how governments intend to respond in the event of an emergency.” Methods exist to elicit community values and discuss policy objectives, such as citizens’ assemblies, panels, and juries.

Incorporated into Hallett’s proposed new independent statutory body should be concrete plans to elicit, codify, and communicate our nation’s values and priorities in future emergencies. These would then underpin a more transparent and effective process for preventing, mitigating, and dealing with future emergencies.

*************************************************************************************

Again, you can read the original article here. I hope to write a bit more about the Inquiry report over the coming weeks as well - this was just one aspect!

I tried to share this to Facebook and they removed it as going against community standards. WTF? Facebook's community standards do not allow assessments of public policy? Really.

I also shared this article on Facebook, only for it to be removed.