Is it "Fit for the future"? The NHS 10-year plan and the social determinants of Health

Labour released its 10-year NHS plan this week - in this post I have a look at whether and how it deals with the social determinants of health

Before the general election exactly a year ago, I wrote a post about the solution for the UK’s health crisis lying in improving housing, income, food security, education and the air we breathe. Yesterday the Labour government published its Fit for the Future 10-year plan for England’s NHS. Many have already written about the plan as a whole, for instance the Health Foundation, King’s Fund and the Financial Times. The general response has been broadly positive in the aims and breadth of the plan but with serious concerns about the feasibility of its delivery, in particular on physical and digital infrastructure and workforce. I agree with both the praise and the concerns - we’ve been here before with the NHS and everyone is somewhat wary of lofty words and ambitions that have failed so often in the past.

One encouraging aspect of the plan is that the social determinants of health are explicitly incorporated and acknowledged as integral to a sustainable future for the NHS. In this post, I will look at what the plan says (and doesn’t say) about those wider determinants of health.

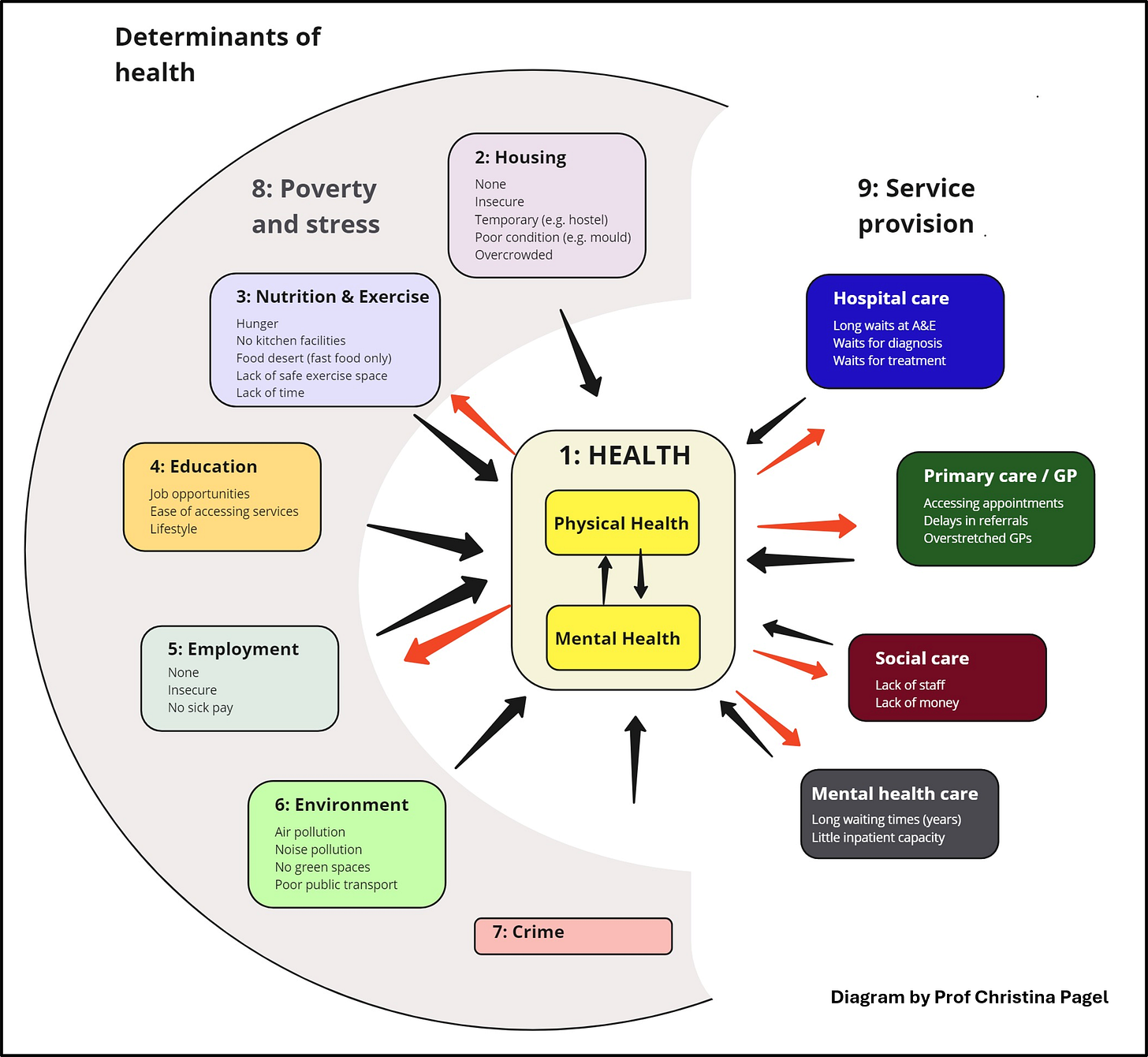

Social determinants of health

Poverty – the fundamental determinant

Low income underlies every lifestyle factor affecting our health, limiting diet, housing, transport and exercise choices. In 2024, 23% of working age adults and 28% of children in the UK were living in material deprivation.

Housing quality & security

Living in insecure accommodation or accommodation that is cold and damp, noisy, cramped or without adequate cooking facilities significantly worsens physical and mental health. The latest English Housing Survey reports that 14 % of households (about 3.5 million) live in a non-decent home (24% for those of mixed White or Black African ethnicity), while housing insecurity has pushed almost 130,000 households (including 81,000 households with children) into temporary accommodation - a record high.

Air pollution – unseen but everywhere

Both indoor and outdoor air pollution can harm every organ in your body with prolonged exposure. Outdoor fine-particulate pollution (PM₂.₅) has fallen significantly over the past 20 years but still averages an annual concentration of 7.2 µg/m³ at urban-background sites. Despite being a record UK low, this is still above the 2021 WHO guideline of 5 µg/m³ and is implicated in an estimated 48,000 premature UK deaths a year. Indoors, cooking with gas, wood burning stoves and build-up of fine-particulate pollution also cause significant health problems, especially as we spend most of our time indoors. Health impacts include respiratory, heart and cognitive problems and children are particularly vulnerable.

Nutrition

Obesity and poor diet are a risk factor for many diseases, include diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, cancers, and musculoskeletal issues. All of these are placing an increasing burden on NHS resources. While of course lifestyle choices impact obesity, it is welded to the geography of deprivation, where fast, processed foods are cheaper and nearer than healthier alternatives and don’t require cooking facilities. Putting obesity down to willpower is facile and wrong. In 2024, 15% of UK households experience food insecurity and over 20% (14 million) have limited access to fresh groceries. The Broken Plate 2025 report from the Food Foundation shows that healthy foods are twice as expensive as less healthy options calorie for calorie, and that healthy food prices have risen much more than less healthy options. Adult obesity is 36% in the most deprived neighbourhoods versus 22% in the least deprived (overall 29 %). For children, the differences are even more stark, with 29% of Year-6 children in the most deprived areas being obese compared with 13% in the least deprived.

Other determinants

The list above is hardly exhaustive - for instance, some other key determinants of health are education, employment, green spaces, noise pollution.

NHS 10 year plan and social determinants of health

If you only read the executive summary, the Plan seems very light on the social determinants of health. But in fact, the full plan does tackle it - and I think it’s a real shame that this hasn’t made it into the executive summary. It is a very good thing that the Plan directly references Prof Sir Michael Marmot’s review on the social determinants of health in its chapter on moving to a focus on prevention and it follows through with policies aimed at going beyond a narrow view of health. It is, for instance, encouraging to see a case study devoted to Greater Manchester’s “Live Well” initative on a cross-sectoral approach to improving poplation health. However, some important gaps remain.

Housing

The Plan discusses the negative health impacts of “cold, damp and mould” and references Labour’s £13.2 billion Warm Homes Plan plus a new proposed duty on social landlords to fix hazards quickly, starting with damp and mould. Labour is also tackling housing insecurity with its Renters’ Rights bill that would abolish section 21 (no fault, sudden) evictions, provide protections against rent increases intended to force out renters and improve minimum standards of private rented accommodation. The £39 billion pledge to build 180,000 new social and affordable homes will also improve both the quality and availability of housing. In addition, the Plan acknowledges the importance of green spaces and opportunities for active transport and is partnering with other government departments and external organisations to improve these aspects. Together, these measures should improve conditions for many low-income tenants and improve health. Of course, this depends on these policies being delivered but it is really encouraging to see these policies within an NHS plan.

Air pollution

The Plan promises to “work with Defra” on a refreshed national strategy, phase down the dirtiest domestic burning, and embed PM₂.₅ targets in NHS messaging - good news for outdoor air and wood-smoke hotspots. It also discusses the government’s plans for cleaner transport reducing pollution (and noise) from vehicles, referencing its investments in the Bus Services Bill and Passenger Railway Services Act. But it says very little on indoor air pollution, outside of tackling damp and mould, and this remains a gap in the plan. The danger of, as one expert said last month, “sleepwalking into an indoor air crisis”, remains.

Nutrition

The Plan talks of a ‘moonshot to end the obesity epidemic’. I am automatically suspicious of such language - and it is also the bit I am most disappointed with. The headline plans are about reducing consumption of ultra-processed foods and high energy drinks through advertising bans, increased taxes, and some outright bans such as on selling high-caffeine energy drinks to under 16s. These measures can work, and the first ‘sugar tax’ on drinks introduced in 2016 led to a significant decrease in sugary drinks sold by 2024. But, much more needs to be done. While there is also an emphasis on increasing the value of Healthy Start vouchers and improving free school meal provision, this does not go far enough in actually making healthier food choices affordable and accessible. How will food deserts be addressed, or the lack of adequate cooking and kitchen facilities in the poorest households (especially for those in temporary accommodation)?

Poverty

Poverty underlies almost all the social determinants of health, and without pulling significant numbers of households out of poverty, the plan’s impact will be reduced. The Plan does have some important measures, such as the Healthy Start Vouchers and increased access to free school meals, alongside some potentially important schemes to increase employment. But the truth is that there are no increases to Universal Credit, little additional help on childcare costs, public transport fares, and no moves to lift the two-child cap on some benefits. The UK is struggling economically, but lifting more people out of poverty is crucial for our long term health and that of the NHS.

Conclusions

In sum, Fit for the Future clearly acknowledgres the social determinants of health in securing a sustainable future for the NHS and better health care provision for us. This is good news and I applaud it. Delivery then, not design, is the biggest concern - the health of the next decade’s NHS depends on whether Treasury and Whitehall match these words with the cash and clout they need. As other commentators have said, those working in health, and particularly public health, have seen promises crumble in the face of reality too many times before.

Thanks to Christina for such a clear analysis highlighting the contributions of social determinants to health and how the NHS 10 year Plan addresses these; and in such readable language! 👍🏾

Great summary Christina, thank you. I too am encouraged by the plan, but as you rightly point out, poverty underlies every aspect of poor health. Until this is dealt with the problems will persist. Likewise, until a government is prepared to be brave enough to tackle the food industry, obesity will not go away.