Is the current Covid wave in England peaking?

Yes - probably. Plus looking ahead to the future.

England is short on Covid data. This is extremely irritating, especially when we are in the middle of a significant Covid wave. It means we can’t say anything for sure but are forced to search for clues in the sparse and imperfect data that remains. This week, that comes down to UKHSA data on hospital admissions in England with Covid, Scottish wastewater data and Covid variant sequencing on very few samples.

Hospital admissions

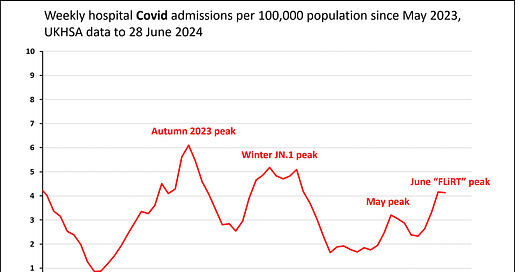

The latest data shows that the most recent week to 28 June was flat - which hopefully signifies that we are at, or have just passed, the peak.

This wave has been substantially bigger than May’s one but so far - in terms of admissions - lower than the peaks at the end of 2023. While hospitals are testing far less than they used to, hospital testing practices should have been stable over the last year, making the waves in admissions comparable.

My prediction from early June held up well I think, where I said to expect a June wave that would be bigger (in terms of hospital admissions) than May’s but lower than December’s.

Variants

We are not sequencing very much at all now (just positive PCR tests from hospital patients really, which represent mainly older people). That said, the data suggests that the “FLiRT” variant KP.3 is dominant in England and has been for a week or two.

KP.3 is very able to evade existing antibodies to infect people and has been causing large waves all around the world. However, there is no indication it is more severe.

Wastewater

Scotland is still monitoring wastewater for Coronavirus - and fhe hundredth time, England should be too (and for H5N1 (Bird Flu) too!). Its most recent data up to 26 June shows sharp increases and no sign yet of peaking.

Virus levels in wastewater are not directly related to number of people infected - a lot depends on viral loads (how much virus an infected person sheds, which varies a lot person to person and infection to infection) and how much of the virus is in your gut (and so gets excreted out). But certainly, it looks as if this is a significant wave with a significant minority of the population infected. We would need the return of the ONS Infection Survey to be sure, and sadly we don’t have that any more.

England normally sees new variants a few days before Scotland (because of travel and population patterns), so I suspect that England’s wave is just peaking (or has just finished), especialy because KP.3 has probably been dominant a couple of weeks already. But because of the Scottish wastewater I am not certain, especially as there will be plenty of mixing happening to watch the football.

Summary

England is in the middle of a large Covid wave, hopefully just starting the downward slope. Hospital admissions are lower than they were during 2023 peaks, and fortunately this wave came not long after the Spring booster campaign which will have protected many in our most vulnerable populations. For an update on the Spring booster campaign please see this substack from Bob Hawkins.

Although it’s good that hospital admissions are nowhere near what they were at the pandemic’s height, waves of infection are never good news. Many people will be off work while sick and some (perhaps 1-2% of infected people) will go on to develop new Long Covid. The percentage developing new Long Covid has come down because of vaccination and previous infection, but it is not zero and there are still few effective ways to treat Long Covid.

It is also self evident that Covid is in no way a winter respiratory bug - its behaviour is nothing like flu or RSV, the other main respiratory viruses that can cause severe illness and do every winter. While flu and RSV are pretty much confined to November to March, Covid waves can and do happen at any time of year. We are still in three to four waves a year, each causing some disruption to people’s lives, employment and the NHS.

Looking ahead

Today sees a new Labour government in the UK. While the incoming government has a massive challenge on its hands across all policy fronts, I hope that this will represent an opportunity for a reset in how we think about Covid and airborne diseases more broadly (particularly with the threat of bird flu (H5N1) ever present).

Committing to cleaner indoor air would be an important public health step, with many benefits in reducing circulating viruses but also environmental irritants, and improving wellbeing and concentration, as laid out in a detailed report from the Royal Academy of Engineering in 2022. Promoting the use of masks in health care settings and public transport during waves could be useful. These measures won’t get rid of Covid waves, but they should help blunt their impact - and help slow down the spread of winter viruses and any new airborne diseases.

Additionally, restarting wastewater monitoring (for all sorts of viruses) would be extremely helpful for giving us early warning of issues and tracking levels of different infectious diseases in the UK.

We urgently need more research into how to prevent and treat Long Covid. We need better, longer lasting, vaccines that are more variant proof - for instance developing new vaccines based on T-cells as explained here by Prof Sheena Cruickshank.

Finally, the government needs to think about its pandemic plan. It is likely that at some point in the not too distant future, bird flu (H5N1) evolves to be able to spread easily among humans. As Prof Adam Kucharski reminds us, we need to plan for this - what have we learned from Covid that we could use for a flu pandemic? What would need to do differently? How do we prepare support and communications to enable the success of prevention and control measures?

Thank you for your report. I just hope this new Govt will take the points you and other reputable scientists have raised and consider the importance of public health. A healthy nation is a productive nation in every respect. I don’t ever want to hear a repeat of the views held by the previous Govt!

In Portugal, the curve of (confirmed) notifications of COVID new cases is also slowing down (decreasing slope). The value of Rt is still slightly above 1, but I expect that we might be passing the peak next week (variation 0%, Rt=1).

Assuming that the level of underreporting remained stable in the past 2 months, a few things can be said regarding the Portuguese KP* wave.

Cases started to increase in early May. The rate of variation hit the peak in middle May (approxim +13.5% a day) with an estimated Rt ~ 1.5, which means cases were doubling every 5 days.

By the end of May, Rt ~ 1.3 (doubling every 12 days), and by the end of Junhe, Rt~1.05.

What might have caused this? The Portuguese reference lab reports that throughout May, the KP.3 lineage became dominant in samples. Simultaneously, humoral population protection was probably already very low in April, as the last vaccine campaign took place more than 5 months ago (with a coverture of only 56% in 60+).

What amazes me is that this virus manages to have an Rt ~1.5 in the middle of a sunny springtime! when most other respiratory virus have already Rt <<1. SARS-Cov-2 has such an high transmissibility that it cares very little for weather seasonality. What appears to determine whether we will have another wave or not is the combination of the ability of new sublineages to evade antibodies with how long ago was the last vaccination campaign (or the last wave).

If humoral population protection is low, a big wave is only a matter of mutational chance and therefore almost unpredictable. Manuel Gomes, Portugal