What is the impact of Long Covid in the Omicron era?

Risks of LC much reduced since 2020, but high number of infections means LC remains a significant issue and research shows lower quality of life and higher health care use.

The last month has seen a couple of Long Covid papers come out, both looking at large adult populations in England.

One, published in Nature Communications, comes from the Imperial REACT study and the other, out as a non-peer reviewed preprint, and on which I am co-author, uses health care records from the whole English adult population. Both studies have control groups of a) people who have never tested positive for Covid and b) people who had Covid but recovered within four weeks. Together they provide an excellent overview of both previous and current risks of developing Long Covid and the ongoing impact of living with Long Covid.

In this post, I’ll summarise the main results and what they might mean going forward. I’ll also reflect on what should have been done differently within science advice during 2020 and 2021, given what we know about Long Covid.

The REACT study looks at almost 300,000 adults in England enrolled between summer 2020 and March 2022 and assesses the likelihood of developing Long Covid depending on variant, age, sex, vaccination, demographics, health status, and severity of covid infection. It also assesses duration of Long Covid, frequency of reported ongoing symptoms and impact on quality of life.

The UCL study looks at health care use among almost 300,000 adults with Long Covid in their medical records compared to over a million people who had Covid but no recorded Long Covid, a million people’s health care use pre pandemicm, and a million people post-pandemic with no recorded Covid infection.

Prof Sheena Cruickshank also did a good post on Long Covid a few weeks ago, which includes some of the underlying physiological mechanisms.

Likelihood of developing Long Covid in the past and in the future

The original variant of Covid, which hit us when we had no treatments, no vaccine and no previous immunity, was shockingly devastating in its long term impact. The study reports that 23% of people infected with the original variant before December 2020 developed persistent symptoms lasting at least 12 weeks, and 16% symptoms lasting longer than a year.

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) infection survey combined with an Imperial modelling study estimates that just 13% of the English population had been infected by December 2020. Even so, by the end of Dec 2020, over 75,000 people had died of Covid and about 1,300,000 adults might have developed Long Covid. Imagine the consequences if the virus had been allowed to "‘let rip” as some were advocating for.

As Covid evolved and people acquired some immunity from both previous infection and vaccination, the likelihood of new Long Covid fell. By the Delta wave in 2021, only 10% of infected people developed symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks (4% symptoms longer than a year). With Omicron (and boosters) this fell further, with only 3% of Omicron infections resulting in symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks. Unfortunately REACT stopped being funded in March 2022 and so we don’t have longer term data on Omicron, but it is likely that the incidence of new Long Covid now is somewhere between 2-3% (ONS for instance reported a rate of 2.4% for new Long Covid in adults following a second infection).

So the good news is that the chance of developing Long Covid is now almost 90% lower than it was in 2020. BUT, the bad news is that many many more people are getting infected. The ONS Infection Survey estimates that since Omicron arrived there have been enough new infections to infect everyone in England at least once. With around 44 million adults in England, 2.5% would translate to a bit over a million new cases of Long Covid under Omicron - similar to the number for the original variant in 2020 (a number consistent with ONS Long Covid snapshot prevalence estimates). So while risks for indidivuals are much lower, the societal impact remains high.

There is one more bit of positive news though - if you develop Long Covid lasting at least 12 weeks now, you are likely to recover significantly sooner than if you’d developed it in 2020.

Other risk factors for Long Covid

Similar to previous studies, there were clear risk factors for developing Long Covid, after adjusting for all other factors. The biggest risk factors were: having at least 2 other pre-existing health problems; having severe illness during the acute phase of illness; and female sex.

Interestingly, and unlike other studies, this team did not find a clear signal for protection from vaccination but they hypothesise that vaccination might be protective by making initial disease less severe and so its effect is accounted for in the “severity of initial illness” factor, which is very impactful.

Main symptoms of Long Covid

All groups (both Long Covid and controls) had relatively high levels of persistent symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, muscle pain. But before you say “A-ha, nothing to see here”, the REACT study team reported 20 different symptoms that were all significantly more common in people reporting Long Covid compared to controls. In particular: change/loss of taste and smell, shortness of breath, severe fatigue and difficulty concentrating/thinking were 9x, 7x, 6x and 5x more likely in the Long Covid group vs control groups respectively.

Impact of Long Covid on quality of life

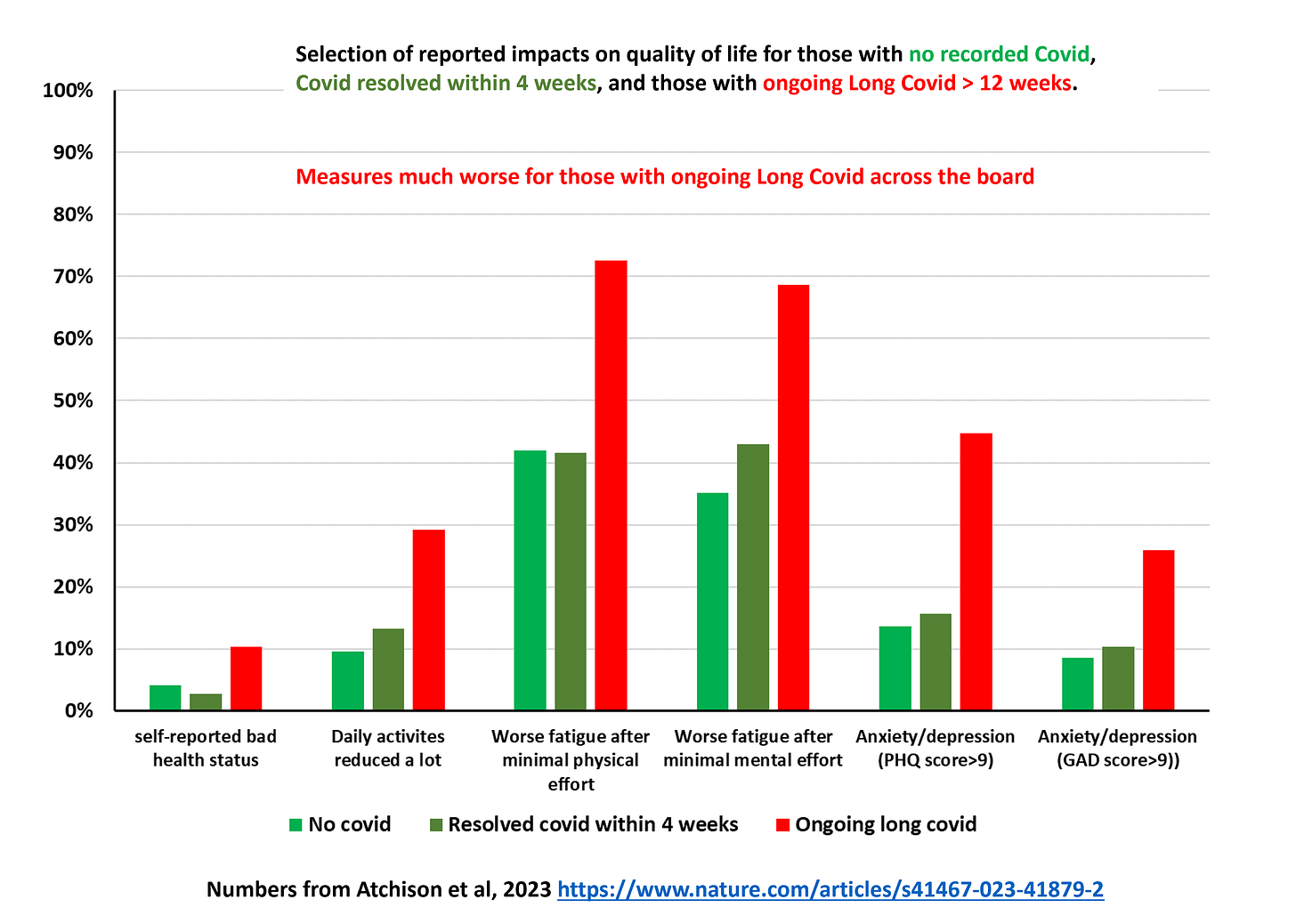

The REACT study team illustrated significantly worse quality of life measures in those with ongoing Long Covid across a range of measures. Particularly worrying are the high levels of anxiety and depression in those with Long Covid and that the large majority of those with Long Covid experience worse fatigue after mild exertion (physical or mental). A key take away for those with Long Covid is not to try to do too much too soon and to pace yourself. And friends & relatives of those with Long Covid - suggesting that a walk might do them good is most likely not helpful!

Certainly these results are consistent with the impacts reported by the ONS Infection survey and the concerns about the impact Long Covid is having on the labour market. There is some good news though - people who have recovered from Long Covid have similar quality of life scores to controls. We must redouble efforts in effective treatments of this illness!

Impacts of Long Covid on health care services

The UCL study looked specifically at use of health care services of those with Long Covid mentioned in their medical record and compared this population to a selection of control populations, matched on age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation, region and pre-existing health conditions. In this post, I’ll just concentrate on the comparison to those with no recorded Covid infection before 1 April 2022. Use of all measured health care services was significantly higher in the Long Covid population (two uses shown in the chart below), with overall annual costs estimated to be 2.5x higher for those with Long Covid than those with no recorded Covid infection.

Most of the additional healthcare use was in the first two months after diagnosis of Long Covid, but increase use persisted over the two years of the study. With well-documented crises in GP provision, hospital bed capacity and record waiting lists for NHS treatment, the additional demand from people living with Long Covid is far from trivial.

Summary

These two studies, based on large cohorts of adults in England and with a variety of control groups, highlight the burden of Long Covid both on individuals and on society as a whole. While the individual risks of developing new Long Covid are far lower now (perhaps around 2.5%) than they were in 2020, the high ongoing prevalence of infection sadly ensures that thousands more continue to develop Long Covid, although hopefully many will recover over time. Added to new people developing Long Covid are the hundreds of thousands living with persistent symptoms for years now and with little in the way of treatments to offer. Many have had to give up their jobs and restrict their daily lives in response.

It was clear by autumn 2020 that Long Covid was a serious issue, and not just for those severely ill in the acute phase of the illness. At this point we should have incorporated Long Covid as an adverse outcome in the SAGE models but it never featured – not even by 2022 when SPI-M modelling ended. This skewed the whole pandemic response to avoiding hospitalisation and death (important outcomes but not the only ones) and away from avoiding transmission. In countries with high levels of infection, particularly in 2020 before vaccination, Long Covid is casting a long shadow, causing acute misery for millions of people and significant drag on the economy.

Imperative now is to understand better the physiological mechanisms behind Long Covid (and there are likely to be several) and invest in research for prevention and for treatments to enable those with Long Covid to return to their former lives.