Updated estimates of Long Covid in England and Scotland show that it remains a serious issue

The UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) has released its latest estimates of how many people in England and Scotland are living with Long Covid using the recent Winter Infection Survey. These are the first good estimates of levels of Long Covid for over a year - the previous update was in March 2023 with the final ONS Coronavirus Infection Survey report.

While the ONS headline numbers are for Long Covid of any duration (i.e. over 4 weeks), I will be concentrating on its data for self reported Long Covid lasting at least 12 weeks. This is more consistent with international definitions and doesn’t include those whose acute symptoms linger for several weeks (such as a cough that takes several weeks to go away completely).

Headline numbers for people with Long Covid lasting at least 12 weeks

Using the most recent data (collected 6 February - 7 March 2024), ONS estimates that about 1.1 million people over 3 years old in England and Scotland are living with Long Covid for at least 12 weeks, representing just under 2% of the whole population. Note that ONS have excluded people who answered “don’t know” to the question on how long their Long Covid has lasted, and so the true number with symptoms for more than 12 weeks is likely to be considerably higher (~1.7-1.8m). See my postscript at the bottom of this post for more details.

In the chart below, I’ve plotted the percentage of the population affected within age gruops, by deprivation and by employment status. Long Covid continues to hit the middle aged the worst, with an estimated 3% of all 45-64 year olds reporting symptoms lasting at least 12 weeks. Children are the least likely to have Long Covid, but prevalence is still 0.6%, representing about 65,000 children.

The inequality is also stark - reported rates are much higher in people living in the most deprived areas of the country, almost twice as high as those in the least deprived.

In terms of employment status, it’s striking that the rates of self reported Long Covid in those of working age who are not employed and not looking for work are almost three times as high as any other category. We can’t tell from this data whether this is because they were already out of work and more at risk of developing Long Covid or whether developing Long Covid drove them out of work, or a mixture of both. But I think it likely that Long Covid is preventing many from returning to the workplace.

Most people with Long Covid have been living with it for years

Of those who currently have Long Covid (>12 weeks) , over 50% have had it for over 2 years, and over 80% for over a year. However, almost a fifth have developed it over the last year. Most of those who developed it in 2023 are likely to have been on their second or more infection and / or been vaccinated. This shows that while the chances of developing new Long Covid might have significantly reduced since 2020, they have not disappeared. Note that ONS does not ask people about resolved Long Covid, and so we can’t use this data to say much about the length of time to recovery (because the recovered are not in the data).

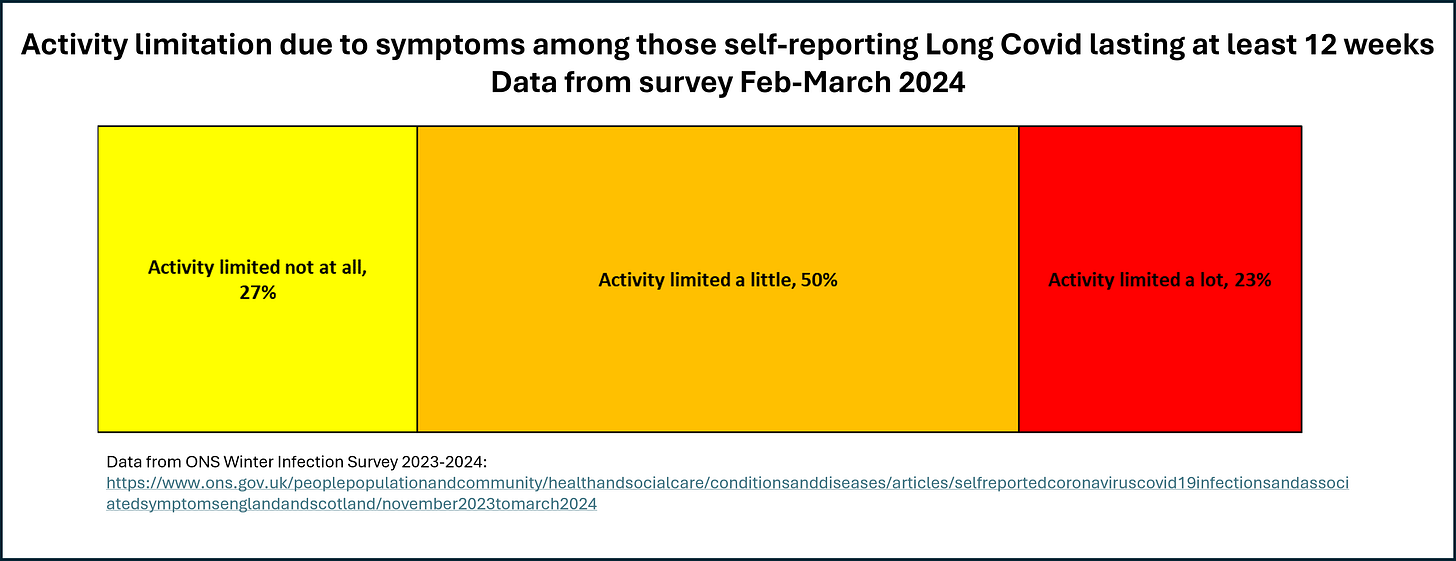

Over a million people having Long Covid would be less concerning if it had minimal impact on their lives. But it doesn’t. Almost three quarters (73%, estimated 630,000 people) have at least some limitation to their day to day activities due to Long Covid. Almost a quarter (23%, estimated 200,000 people) have their day to day lives impacted a lot.

ONS reports the most common symptoms reported by those with Long Covid as weakness or tiredness, shortness of breath, difficulty concentrating and muscle ache. Over half said their symptoms worsened on physical or mental effort. Over half were experiencing at least five symptoms. We still lack effective treatments for far too many people.

Changes in the prevelance of Long Covid over time

The ONS Winter Infection Survey asked people about their ongoing symptoms four times between November 2023 and March 2024. Over those few months, the number reporting symptoms lasting at least 12 weeks was fairly constant, but the 12 week lag means that the survey would not capture anyone developing new Long Covid after infection in the large 2023 Christmas wave.

The headline numbers for people with Long Covid for at least 12 weeks in March 2024 are quite a bit lower than those reported in March 2023 (1.9% now vs 2.7% a year ago). However the two estimates are not directly comparable. The main difference is in how ONS calculates duration - in March 2023 they just used the date of a person’s first confirmed Covid infection to calculate duration. This would overestimate duration because it doesn’t take into account that some people would only develop ongoing symptoms on subsequent infections. This year they asked people instead when they think their Long Covid first started, and calculated duration from that.

The difference is quite noticeable. The headline figures for Long Covid of any duration are in fact similar (and have increased) (3.3% now vs 2.9% in March 2023). However, while in March 2023, ONS reported that only 2% of those reporting Long Covid had their infection within 12 weeks, this year ONS reported that 13% of those reporting Long Covid have experienced ongoing symptoms for less than 12 weeks. This suggests to me that in fact people experience symptoms beyond 4 weeks on their second or more infection more commonly than thought and this would not have been captured in the March 2023 estimates. I thus think that the March 2023 estimate of 2.7% of the population experiencing symptoms beyond 12 weeks is a significant overestimate.

Given the headline figures for self reported symptoms beyond 4 weeks (a more comparable number across years), I suspect that the number with Long Covid for more than 12 weeks in March 2024 is also similar to last year, despite the apparent difference in reported numbers.

Summary

Long Covid risks being forgotten about because there are hardly any reliable measures of it and because of the uncomfortable fact that there are broader consequences of waves of infection, even if acute illness is much reduced. The ONS Winter Infection Survey (and the Infection Survey before it), especially because they regularly tested a representative random sample of the population, are incredibly important sources of data for tracking Long Covid. I hope the Winter Infection Survey returns next winter.

In the meantime, as Prof Danny Altmann and I wrote about a few months ago, research into the causes, prevention and treatment of Long Covid remains urgent.

PS NOTE

I’ve used data for people with Long Covid symptoms lasting at least 12 weeks throughout because that is the most accepted definition. However, note that the ONS data excludes those who don’t give an approximate date for when their Long Covid started, which is about 34% of people reporting Long Covid. This is quite a lot. Apologies for not including this detail in the first version of this substack.

It is likely that many of those who say “don’t know” or “prefer not to say” first developed it more than 12 weeks ago (not least because 87% of those who *do* give a date, were more than 12 weeks ago). Thus a better estimate of the number of people with Long Covid for over 12 weeks is likely around 1.7-1.8 million. There is no reason however to think that the proportions by demographic indicators (shown in the first chart above) are that affected (and they are not so different to the proportions for all people).

That said, it is also likely they they represent a “milder” Long Cohort, as those with very severe Long Covid might be expected to remember better when it started (and their life changed). This is borne out to some degree in the data - of those who say “don’t know” *or* say they are less than 12 weeks from developing Long Covid, 16% say it limits their activity a lot vs 23% of those who say they’ve had Long Covid for more than 12 weeks.

The overall message that Long Covid has not gone away and remains an important problem that desperately needs more research into physiological mechansims, prevention and treatment is unchanged.

Thank you for this invaluable summary. As a grandfather of a 11 year old child with LC for 2+ years it is good to see the wider picture. It is debilitating for individuals socially, physically and economically.

Thanks very interesting. I got long Covid after a November 2023 infection, and I know others have too. I wonder it is JN.1, as I was vaxxed about seven times. I'm curious also as to why it is the middle-aged groups with the highest incidence?